Banele Khoza

‘27’

13 February 2021 - 10 April 2021

BKhz, Johannesburg, ZA

Written by: Ayodeji Rotinwa

Five months since his last exhibition, In My Feels, the fourth installment in a career-long meditation on love, sometimes unrequited, on abandonment, often recurring, Banele Khoza has invited us into his innermost reveries, once more, in 27.

Since his last outing, Khoza has experienced some personal and professional changes. He has turned 27. The artist-entrepreneur-gallerist has also moved to another gallery space, leaving the student district Braamfontein for the more upscale Rosebank. Both milestones of course herald exciting new adventures. But some things stubbornly say the same, on the canvas at least: the preoccupation with love, with desire, and in this new exhibition.

Khoza’s work is his heart made manifest not just on his sleeve, but on the canvas. It is a mirror reflecting familiar anxieties, anguish, melancholy, anger, hurt, loneliness, abandonment, navigating love and living in today’s ultra connected yet hyper isolating world. In many ways, Khoza’s work is made, pitch perfect for today’s young person, art enthusiast, collector, who is not uncomfortable with vulnerability, who is unafraid to share, who seeks to earn something, solidarity, a community perhaps, by giving away a little of themselves.

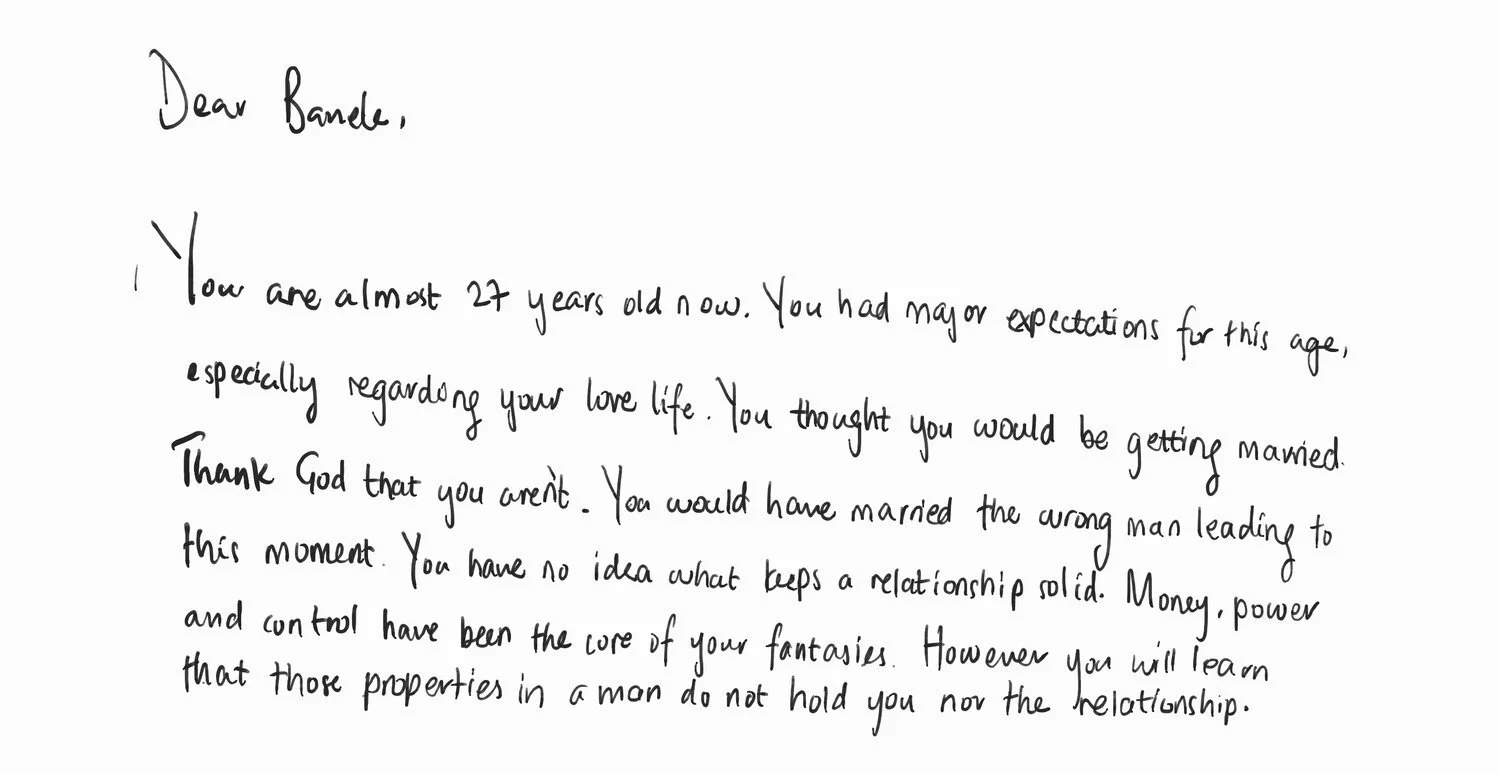

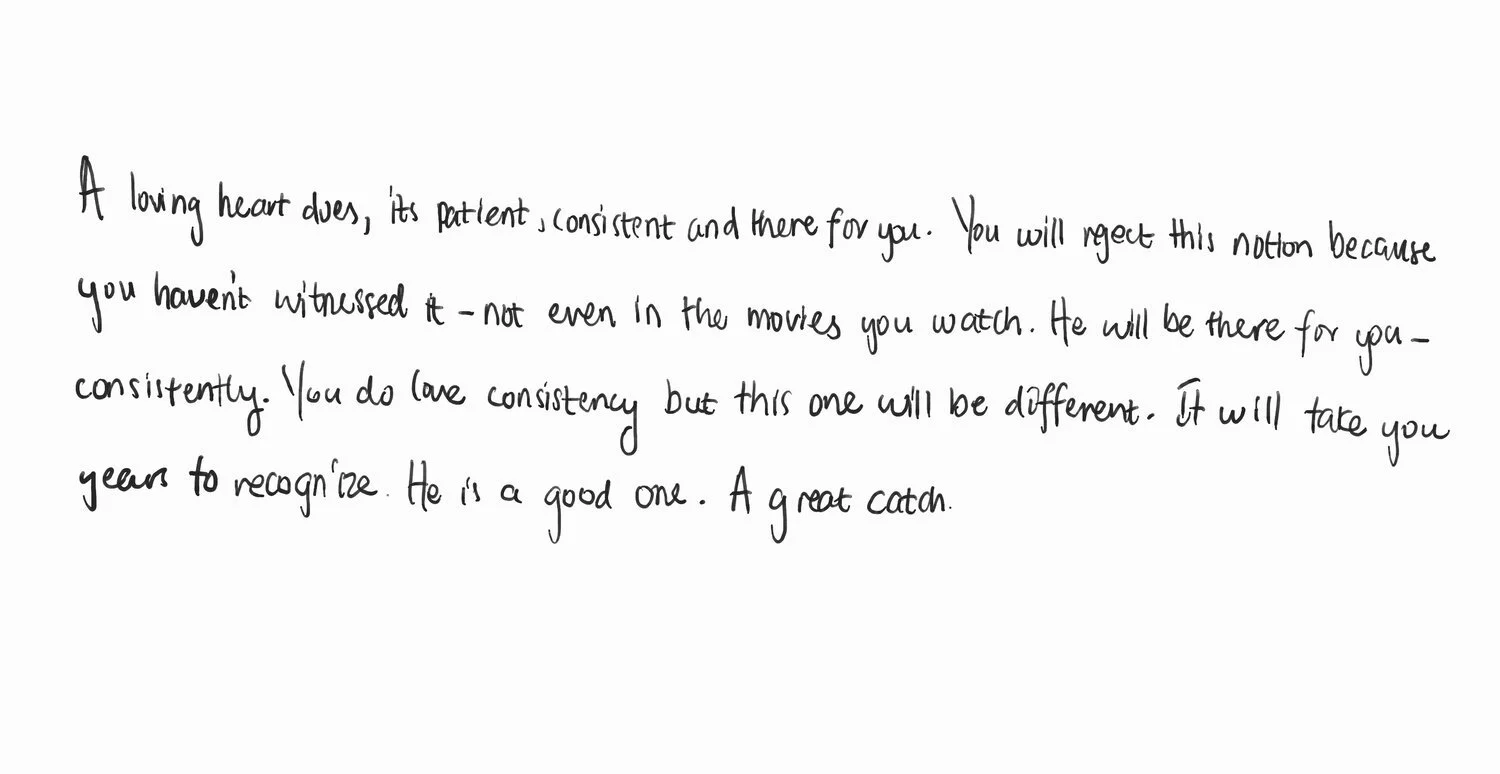

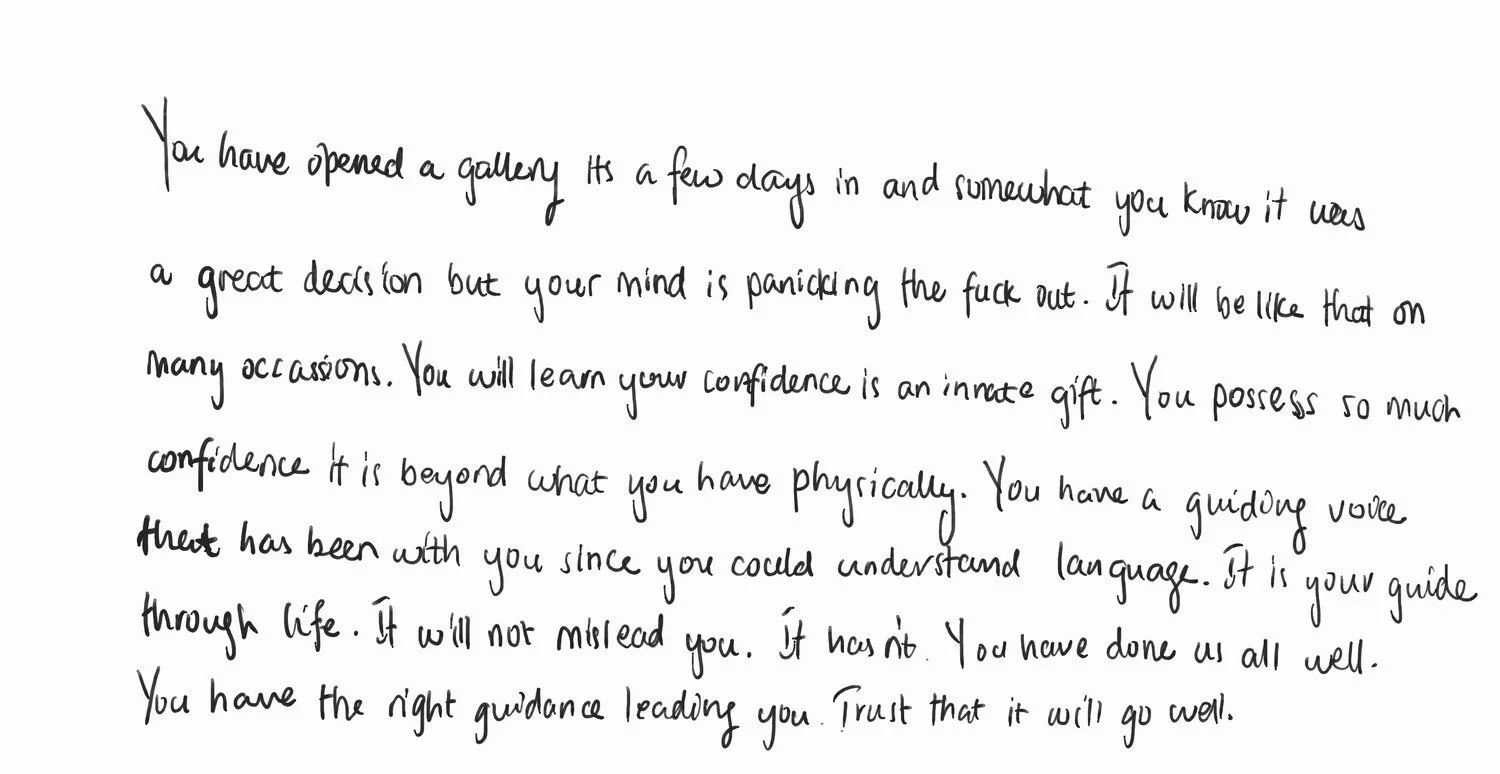

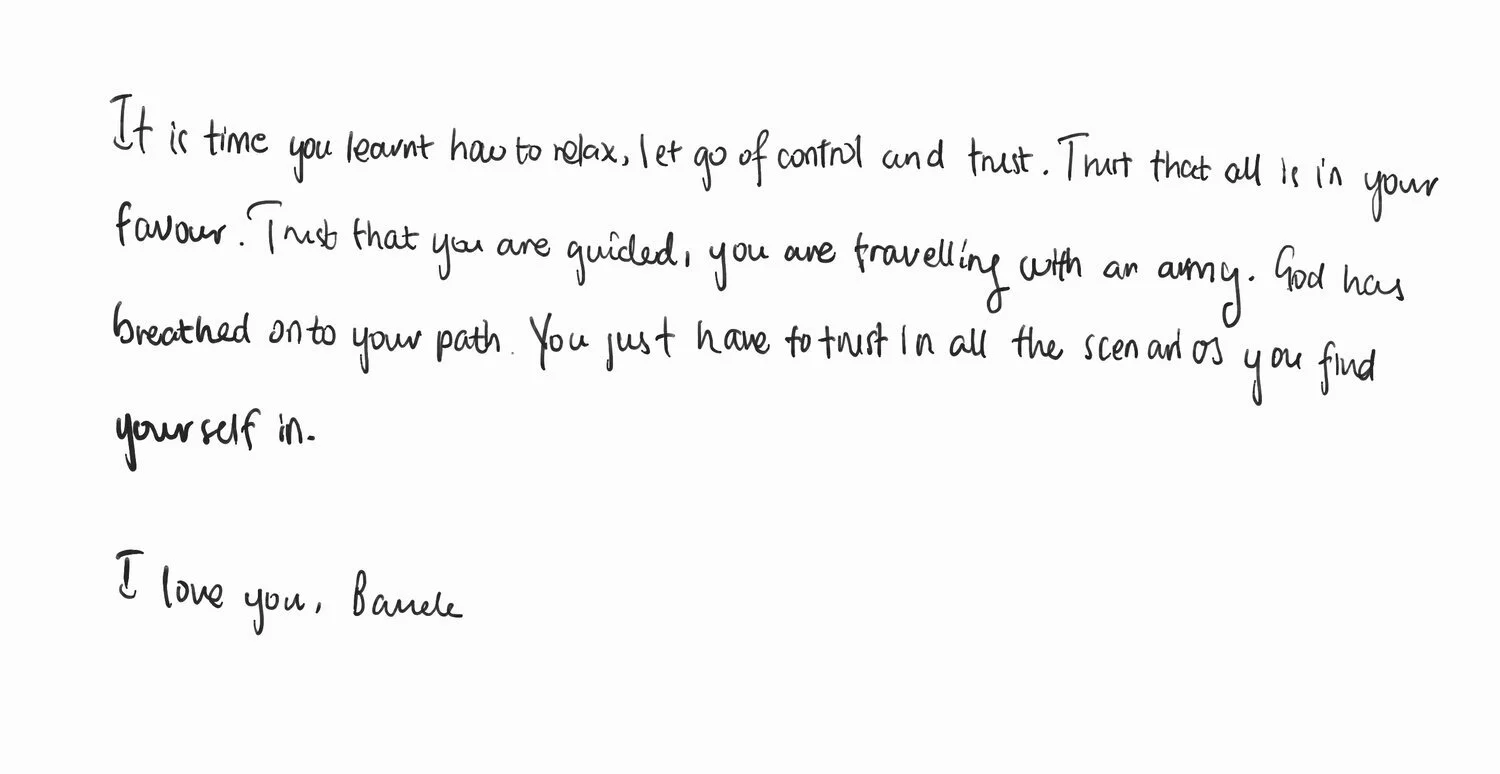

Khoza gives generously. 27, so named for the artist’s new age, starts with a letter.

Khoza has addressed it to himself. The letter is a wind vane, filled with affirmations, telling Khoza and us, readers and voyeurs, where he is going next and what will happen there.

“You will learn your confidence is an innate gift… You have a guiding voice that has been with you since you could understand language...It's time to learn how to relax, let go of control, and trust…”

The letter is familiar. We have chanted them to ourselves in the mirror. We have taped them to our vision board. They are how we acknowledge our failings and how we can overcome them. Like the paint on his canvas, Khoza uses words, though deeply personal to him but widely relatable to set the tone here. But while the words are indeed hopeful, the works that follow in this exhibition are an altogether different proposition and a darker turn for Khoza.

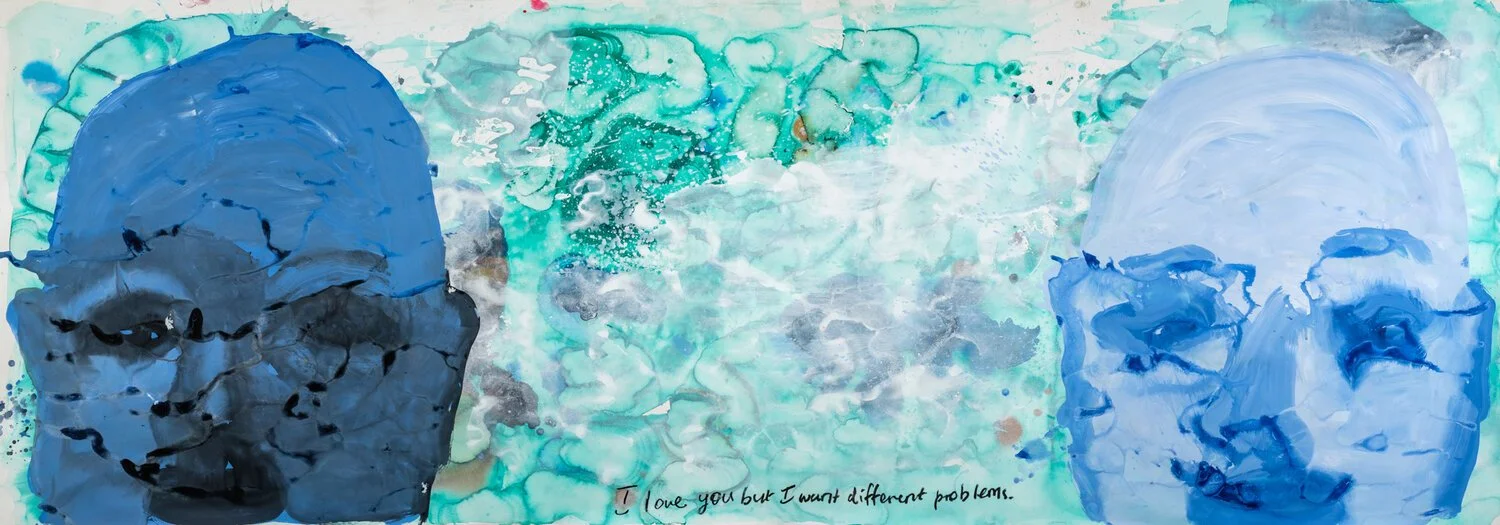

Khoza has always straddled the line between figuration and abstraction, leaning into the former, dipping into a palette of bright, warm, personable colours pinks, blues, purples, yellows, teal to interrogate love’s trials and tribulations. These paintings are sometimes tongue in cheek, with comic captions or words written onto the canvas itself even while addressing weighty matters. 27 does not contain any cheer. Khoza almost completely abandons figuration here, or any attempts at portraiture, realising the male body as he typically does. There are no warm colours either.

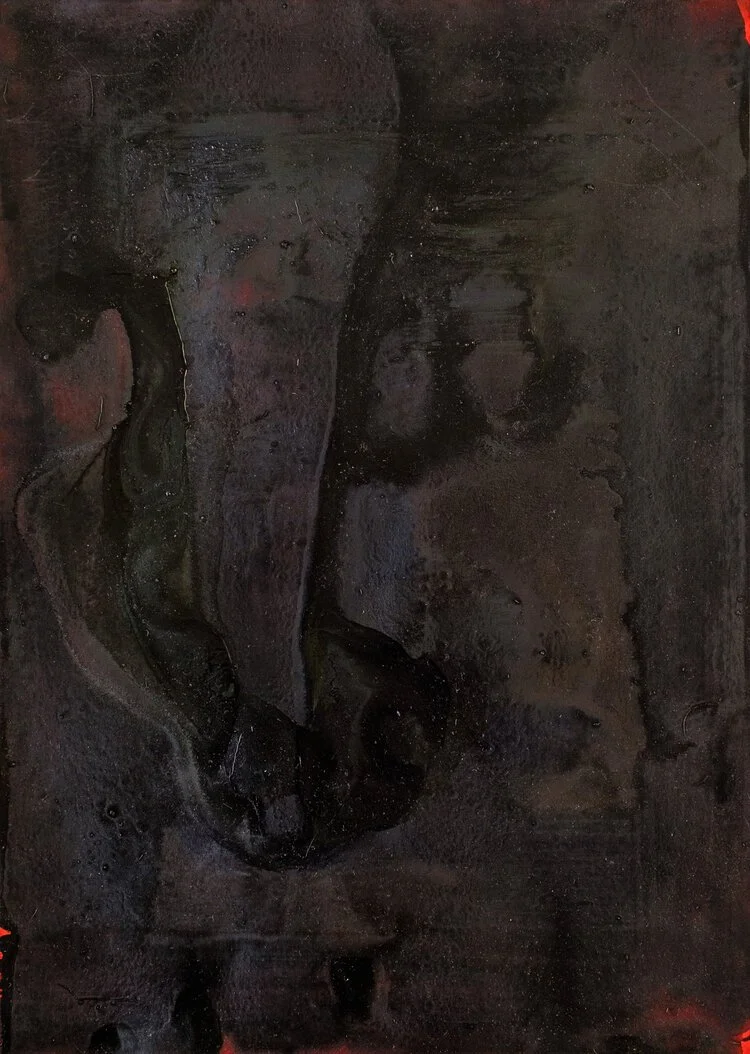

As one enters the exhibition, the first piece down in the line of sight is “What I Wish I Could Tell You,” is a pink, grey and white indeterminable abstraction, in which the canvas resembles an abyss. The work doesn’t start or stop at any discernible point except the canvas’ very borders. You could easily stare at it endlessly. It is perhaps the one of only two pieces in his typical colour palette. Elsewhere, in the precedent area of the gallery, Khoza, instead, uses and has hung broody black paint(ings) to chilling, chromatic effect; mixing with dark browns and green, yellow, orange. In the large “Spring Will Find You Too,” (124 x 22cm) we see what looks like two lovers, embracing, laying on top of one another, on a bed of grass. The caption implies a hopeful turn of events but the dark brown and green figures on the canvas bordered by orange and speckled with black only feel like foreboding. This story is likely not going to end well. Maybe.

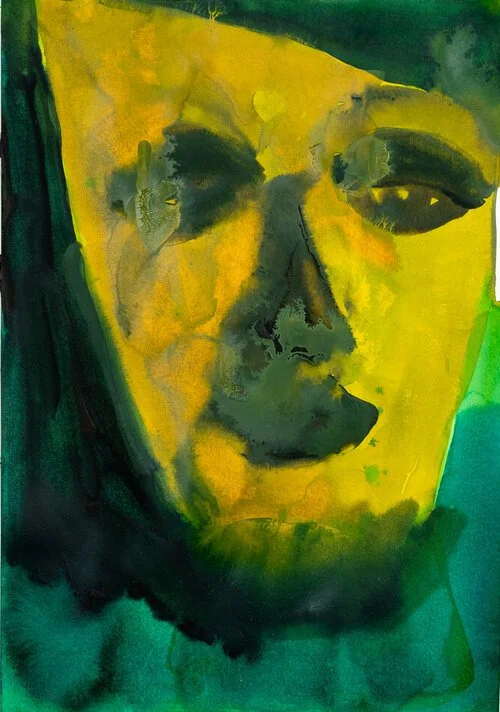

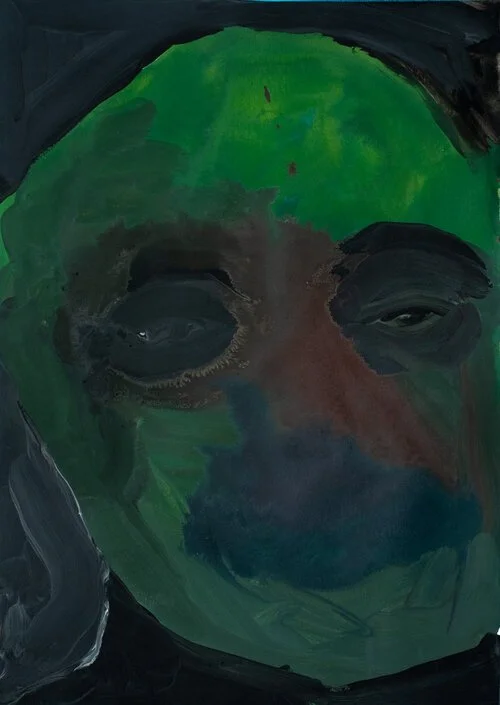

In smaller paintings, the darkness that is still to come is preceded by two small paintings, “Familiar Wounds” and “Love Looks Impossible Today. In the former, are clearly melancholic features of a being, awash in green, black. For an admittedly small 440 x 315mm of canvas, the sadness is still yet stark. In the latter, also similarly sized and equally unnerving, Khoza uses a mix of yellow, orange, black and green paint to searing effect. The colours chromatically rendered combine to depict a love (or woman, or man?) burning, diminishing. It's all dreary tidings at this point but the most saddening is yet to come, still.

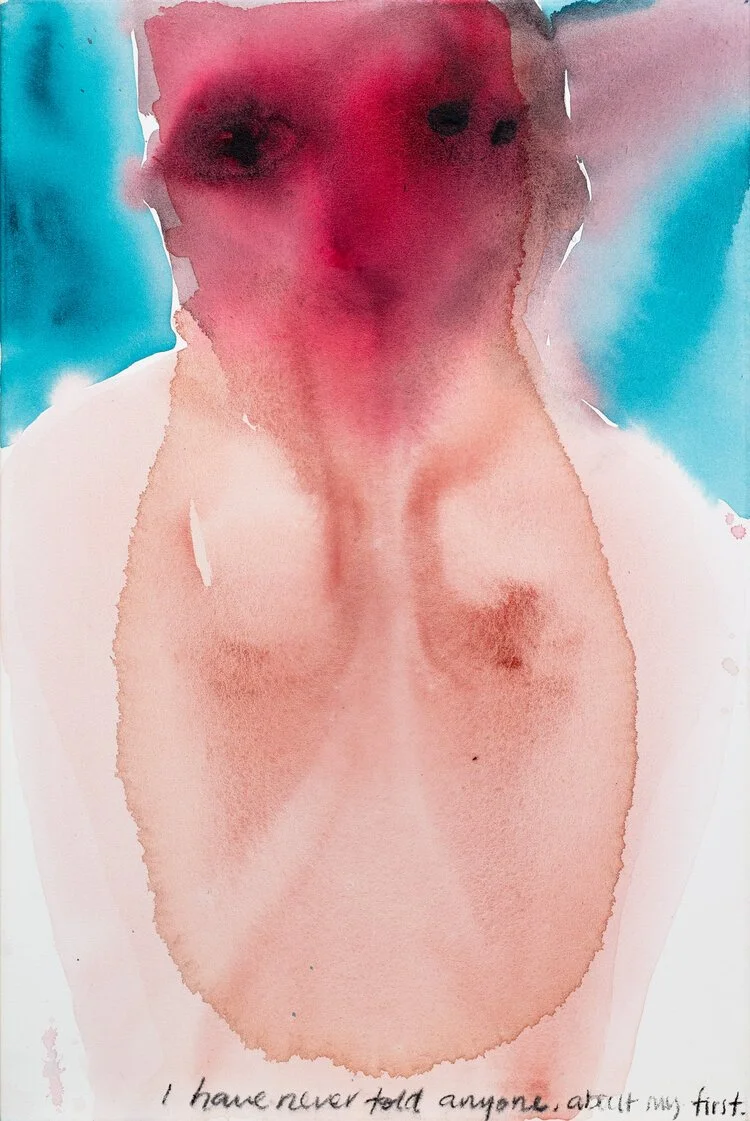

In the narrow hallway of the gallery, further in are more paintings and perhaps the most striking of Khoza’s collection here. They appear as a pair: “I never told anyone about my first” and “He wanted to have me without protection” On the canvas Khoza has used a lurid red bleeding into blues and white space, for the former painting. And all red, touches of black on white space for the latter. This is the real departure point for the exhibition. Where love, abandonment and wringing of hands because of either have been Khoza’s preoccupation, here he broaches something further, the consequences of this love. An aberration. An injury that's more than skin deep. Both paintings seem equal parts of what should be one work, one body. In one, a face, again indeterminate, haunting, a reflection of itself painted underneath it. It is as if his face has melted into another form. In the other, “He wanted to have me without protection,’ we see forms which resemble a pair of legs painted in red, interrupted with a splash of faint white space and black paint at the knees. What is implied in this painting is at once loaded and crushing. The caption signals what Khoza has experienced and is bringing forth here, but the painting drives the wandering further.

Khoza is undoubtedly trusting and his audience more on the canvas. With 27, it comes clearer now that past bodies of work have been holding back a tad. There has been melancholy, yes but reined in on a leash. With this body of work, Khoza has let it go and left it all - thought I suspect there’s more to come - on the canvas. He has gone from mining the seemingly just familiar, to the possibly reprehensible. We are voyeurs, let in on it all, seeing his pain, hopefully past, shaped on the canvas. It is an uncomfortable viewing. But no doubt, an arresting one.

Khoza hasn’t just put his heart on the canvas, he’s bleeding on it too.